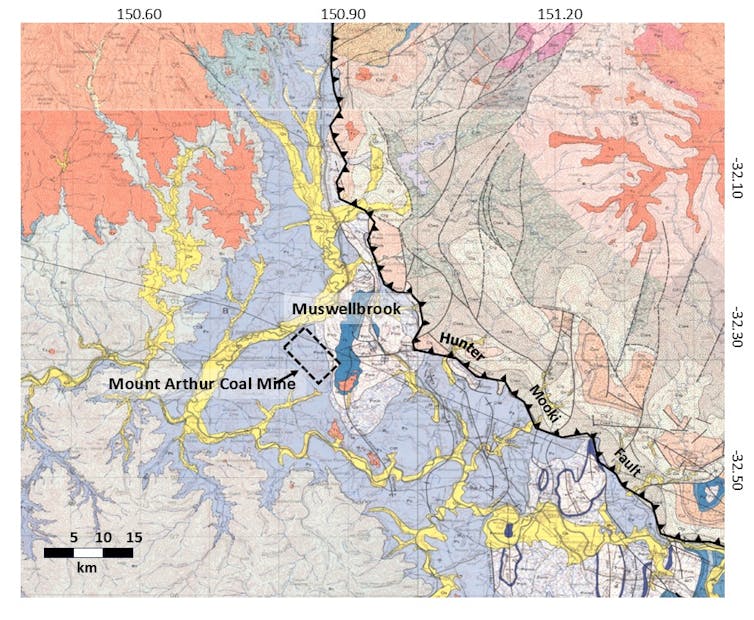

Banner image: Recent earthquakes near Muswellbrook. Geoscience Australia, CC BY

This article was written by Dr Dee Ninis, Earthquake Scientist from Monash University and Dr Dion Weatherley from the Sustainable Minerals Institute's Julius Kruttschnitt Mineral Research Centre. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

On Friday 23 August, a magnitude 4.8 earthquake near Muswellbrook, New South Wales, shook the state. The earthquake caused local damage and Geoscience Australia received more than 3,600 felt reports, including from Sydney and Canberra, up to 360 kilometres away.

Since then, there have been numerous aftershocks, including one of magnitude 4.6 at the weekend. The earthquake sequence is directly under the operational Mount Arthur coal mine, so at face value these earthquakes appear to be associated with local mining. But correlation does not imply causation. Let’s take a look at what we know.

What causes earthquakes?

Earthquakes typically happen when stress builds up in the planet’s crust as a result of tectonic forces. Once sufficient stress has built up, pre-existing weak zones or “faults” in the crust will slide – this is an earthquake. The stress is released as seismic energy waves.

Human activities that produce changes to the stress in Earth’s crust can also cause earthquakes. These are called “induced” earthquakes: without human activity, they wouldn’t have occurred.

“Triggered” earthquakes happen on existing fault structures, but have been brought forward in time by human activity: they would have happened anyway, but the introduced stress made them happen a little sooner.

Human activities that can produce induced and triggered earthquakes include fracking, wastewater injection, the filling of human-made reservoirs, and mining.

In open-cut coal mining, removing large volumes of rock from the surface may change the stresses locally and potentially result in earthquakes.

At the Mount Arthur Coal mine, earthquake monitoring has been ongoing since the 1990s. While a smaller mine was operational prior to that time, satellite images on Google Earth show a significant expansion – more than double the original mine size – began in 2002.

Seismic activity in the region increased from about 2014. This appears to indicate that the crust has been responding to stress changes due to mining at the site.

What has been happening recently at Muswellbrook?

Since Friday’s magnitude 4.8 earthquake, there have been a further 20 events larger than magnitude 2.5. All of these earthquakes have been within 5km of the surface. This is considered “shallow” and may indicate the quakes happened because the removal of coal at the surface changed the stress in the crust.

So, the shallow depth and the possible seismic activity increase since the mine was expanded may indicate these recent Muswellbrook earthquakes were mining-related. But there’s also evidence to suggest otherwise.

A recent study indicates that even large open pit mines do not appreciably change the stress along faults in the near-surface (within 5km depth) to trigger moderate-sized earthquakes. Calculations show faults would need to be already tectonically stressed almost to the point of failure for mining to affect the timing of earthquakes.

However, shallow induced earthquakes are possible. These generally are very small events – less than magnitude 2 – and most occur within a few hundred metres of the mining.

The region had earthquakes before mining

Some earthquakes in the Muswellbrook region may be occurring simply because of the local geology.

Muswellbrook is on the eastern margin of the Sydney Basin, which holds sediments from 200 million to 300 million years ago. These include the organic matter that turned into the coal now being mined. The eastern margin of this basin is the Hunter-Mooki Fault, a complex fault system that spans more than 400km.

North of Muswellbrook, a related fault appears to show evidence of earthquakes in the recent geological past, long before any mining in the area.

The southern extent of the Hunter-Mooki Fault is near Newcastle. Australia’s most damaging known earthquake happened here in 1989, claiming 13 lives. It had a magnitude of 5.4.

If some segments of this fault system have produced earthquakes previously, it’s feasible other faults along this boundary could produce earthquakes too, without any associated mining.

Earthquake clusters are not uncommon in Australia. Between 1886 and 1949, four moderate earthquakes between magnitude 5.3 and 5.6 happened at Dalton-Gunning, NSW, as part of a lengthy seismic sequence. The region still hosts earthquakes to this day. This and many other earthquake sequences are not near mining sites.

Overall, the available evidence for the recent earthquakes near Muswellbrook does not allow us to say unequivocally whether they are related to mining.

Earthquakes can and do happen anywhere in Australia. While mining can induce seismic activity locally, most of these earthquakes will be minor, and are rarely felt. Tectonic forces are still the main cause of moderate earthquakes in Australia.![]()