Can we measure a contribution of mining to the SDGs?

Dr Kathryn Sturman addressed a Roundtable Discussion on Extractives and the SDGs: Partnerships to progress the goals hosted by Cardno, the Columbia Center on Sustainable Investment and the Sustainable Development Solutions Network in Melbourne on 10 April 2018.

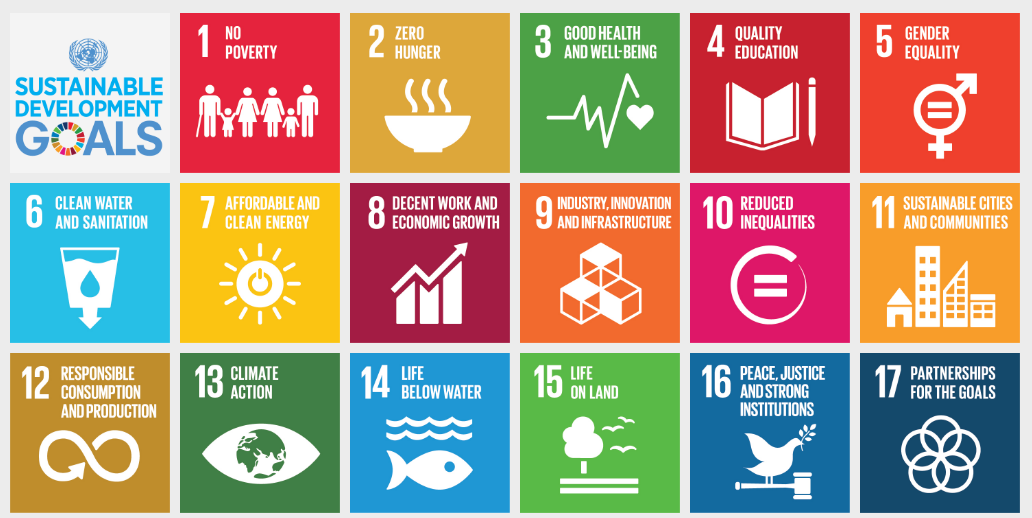

The role of mining, mineral and metal supply chains in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is firmly on the agenda of the OECD in Paris this month and the United Nations in New York[1]. Australia may be far from these high-level meetings, but is one of the few OECD countries located in the Global South. ASX-listed mining and related services companies operate in remote areas of Australia, Melanesia, South East Asia, Africa and Latin America where sustainable development needs are high. Many can show site-level contributions to development in these contexts. But how do we measure the overall contribution with several hundred indicators designed to measure progress towards the SDGs at global and national levels?

There are three challenges to measuring SDG contribution from the mining sector:

- What should be measured?

- At what level should contribution be measured?

- What is already measured as sustainable and responsible mining?

First, a study titled “Mapping Mining to the Sustainable Development Goals: A Preliminary Atlas.” (UNDP, CCSI, UNSDSN, WEF, 2016) has clearly identified what could be measured against each of the 17 Goals. It shows two aspects of sustainability for the extractives industry:

- Contributing to local community and national development by producing raw materials, paying royalties and taxes, employment, infrastructure and corporate social investment (making positive impacts within the area of influence)

- Operating sustainably (avoiding negative social, environmental, governance and human rights impacts)

The distinction between positive and negative impacts of mining is important to align the existing sustainability performance indicators for the mining sector with the SDG indicators. For example, the Global Reporting Initiative, Global Compact and World Business Council have created an ‘SDG Compass’ to guide companies to align business reporting metrics with the SDG indicators. But if a mine manager searches for indicators with the keyword ‘mining’, the results are the following 10 indicators from the GRI Mining and Metals Supplement:

- Number of sites where artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) is on or adjacent to the site;

- Number of significant disputes relating to land use of local communities and indigenous peoples;

- Number of operations on or adjacent to indigenous peoples;

- Number of sites where resettlement took place;

- Existence of grievance mechanisms;

- Amount of land disturbed or rehabilitated;

- Total amounts of overburden, rock, tailings and sludges produced;

- Number of sites requiring biodiversity management plans;

- Number of strikes and lockouts;

- Programs and progress relating to materials stewardship.

A reduction in some of these numbers would indicate improved operations over time, but does not fully capture a positive contribution, such as to poverty reduction from employment and economic linkages, improved community health, peace and stronger local institutions, or net positive impact on biodiversity.

If the search of the Compass is by SDG category, for example, for SDG 16.6 ‘accountable, effective institutions’, the GRI indicators for good corporate governance come up. Participation of the company in the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) in the host country would be a better indicator of a broader contribution to good governance beyond the company itself.

The GRI and other sustainability initiatives do have indicators of positive social and environmental indicators, but they are not specific to mining. It is also more difficult to attribute positive impacts on sustainable development to the actions of a mining company, than it is to show how its operations avoided negative impacts. To align the indicators applicable to the mining sector with the SDGs, we need to be clear and focused on what is to be measured.

Second, we need more thinking about how to channel the data on positive impacts collected within a mine’s area of influence into the data collected at national level and at the global level.

The ICMM has been working to profile this contribution of its members and provide guidance to all companies on how to make and track their contribution to the SDGs. It is a step in the right direction, but fairly easy to gather these good news stories from individual companies. There is more to the contribution of mining to the SDGs than the sum of site-level activities of every mine, as the ICMM acknowledges.

The most successful case studies are, in fact, acknowledged partnerships between ICMM members and host governments, NGOs and civil society organisations. How do we then measure the impact of multi-stakeholder partnerships for development, if the indicators are aimed only at individual companies? In addition, how do we measure the cumulative impacts of many mining companies operating in a resource-rich region, such as the Bowen Basin or the Hunter Valley?

Third, there is no need to reinvent the wheel to measure contribution to the SDGs in this sector. Existing sustainability standards and initiatives for responsible mining and supply chains could be used. There are plenty to choose from. In the last 20 years there has been a proliferation of sustainability initiatives, standards and certification schemes. The sheer number of them now risks causing confusion and increasing compliance costs for companies seeking to improve and demonstrate sustainability performance.

In a project funded by the German government (GIZ), CSRM has mapped a sample of mineral sustainability initiatives to show where greater interoperability may be possible between them[2]. The first phase of the project (2017) looked at thematic scope, assurance processes and sanctions for non-compliance. The current phase (2018) is comparing how 14 different mineral sustainability initiatives monitor and evaluate their impact. The most established in this sense is the EITI, which has been the subject of numerous impact evaluations. The main challenge is attributing change in levels of transparency, corruption and ultimately, sustainable development of EITI implementing countries to the EITI itself. This is a similar problem to measuring the overall contribution of mining to the SDGs.

The SDG indicators framework has already identified existing initiatives with a role in measuring specific SDGs, such as the EITI for SDGs 16.6 and 16.7 (building transparent and accountable institutions; widening political space for stakeholder engagement), and the GRI for SDG 12.6 (to encourage companies to integrate sustainability information into their reporting cycle). We could take this further by mapping more initiatives to the SDGs, such as the ‘conflict minerals’ initiatives and the Voluntary Principles on Security and Human Rights to peace and justice (SDG16), Fairmined and Fairtrade Gold to SDG1 poverty alleviation; and the commodity-specific supply chain initiatives, such as the Aluminium Stewardship Initiative, Bettercoal Initiative and ResponsibleSteel Initiative to SDG12.2 (Achieve sustainable management and efficient use of natural resources).

The next step would be to support each of these initiatives to better design and align their monitoring and evaluation of impact with the tracking system for the SDGs. This would include:

- Clear objectives aligned with specific SDGs

- Robust theories of change

- Indicators aligned with the SDGs

- Annual data collection for all initiatives

- Compatible reporting formats

Lessons for improving the interoperability of mineral sustainability initiatives may be drawn from other sectors, such as the sustainability standards for renewable resources like the Forest Stewardship Council and the Marine Stewardship Council, which meet annually under the umbrella body ISEAL Alliance. Several mining and mineral sustainability initiatives are now looking to the ISEAL codes of good practice on developing standards, assurance and impact monitoring and evaluation and to “common core indicators” they are designing.

In Australia, the newly established EITI multi-stakeholder group could take up the role of data collection and reporting the contribution of mining to the SDGs. The EITI pilot here showed that the complexity of Australia’s federal system of resource governance is a barrier to transparency and public understanding of the contribution of mining to the economy. A structured multi-stakeholder group with representatives from the Commonwealth and state governments, the Minerals Council of Australia and major companies and civil society organisations could be best placed to assess and report the contribution of mining to sustainable development.

[1] The Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN) and Columbia Centre for Sustainable Investment (CCSI) held a roundtable on mining and the SDGs in September 2017 during the UNGA session in New York. The SDSN with Cardno Australia hosted a follow up roundtable on Extractives and the SDGs in Melbourne on 10 April 2018. This article summarises a presentation by CSRM Senior Research Fellow Kathryn Sturman to the Australian roundtable.

[2] Mori Junior, R., Sturman, K., & Imbrogiano, J.-P. (2017). Leveraging greater impact of sustainability governance initiatives: An assessment of interoperability Brisbane: Centre for Social Responsibility in Mining, University of Queensland.