Professor David Cliff has been with the Sustainable Minerals Institute’s Mineral Industry Safety and Health Centre (MISHC) for over 19 years, but his work in the field extends far before that. Without touching on his international experience, David’s health and safety insight has seen him serve as both the Safety and Health Adviser to the Queensland Mining Council and the Manager of Mining Research at the Safety in Mines Testing and Research Station, provide expert testimony to the multiple mine disaster inquiries and provide in-person assistance at over 30 mining incidents.

We sat down with David to talk about health and safety in the mining industry, how it has changed, and where it is heading.

The begining of a career in health and safety

“Initially I was going to become an academic and I did the whole ‘PhD to postdoctoral’ route, but then I got a job at CSIRO researching the combustion characteristics of coal to try and make it burn more efficiently. Rather ironic considering where I am now.

“Initially I was going to become an academic and I did the whole ‘PhD to postdoctoral’ route, but then I got a job at CSIRO researching the combustion characteristics of coal to try and make it burn more efficiently. Rather ironic considering where I am now.

“That led me to join Simtars in 1989, initially to run a research project aimed at trying to identify the presence of hydrogen in mine atmospheres using lasers and fibre optic but, as has been the case throughout most of my career, the work I was doing became very opportunistic.

“At Simtars, we developed expertise in a lot of areas simply because there was a research or commercial gap, and people were asking ‘can you do this’ or ‘how do you do this’. I did a whole gamut of work there, ranging from environmental projects to occupational exposure in all sorts of industries.

“Really, I haven’t actively tried to pursue one area of research across my career, because the work I was doing was always driven by client research needs. Fundamentally, my expertise is in data analysis, applying science, and critiquing and expanding the rigour of that science.”

The early days of dust

“I started working with respirable dust at Simtars in the mid-90s. We tried to continue that work for a long time but it was difficult to get industry and government interested given other priorities, until cases of coal workers' pneumoconiosis started reappearing.

“The more we delved into the science behind respirable dust, not so much the medical side but the monitoring and assessment side, it became clear to me that we didn’t really understand it.

“Although we have been studying coal dust exposure for over a hundred years, maybe 200 years, we have been approaching it from a very agricultural-engineering method rather than a scientific method.

“Prior to 2015, the department didn’t even collect the data from the mines and had no overall perspective on the exposure of mine workers was to coal dust.

“I’ve done a number of reviews, of various sorts, for the Queensland and New South Wales governments, and in those reports I regularly recommended that respirable dust data needed to be collected by the government and reported on from a risk management point of view.

“A lot of the research in recent times has been trying to un-pick things and stop being superficial about what we know and give the issue the attention it deserves.”

Gaps in the Understanding and Management of Particulates

“MISHC’s Gaps in the Understanding and Management of Particulates research program grew out of an earlier ACARP (Australian Coal Association Research Program) funded research project where we focused on looking at underground coal mine dust.

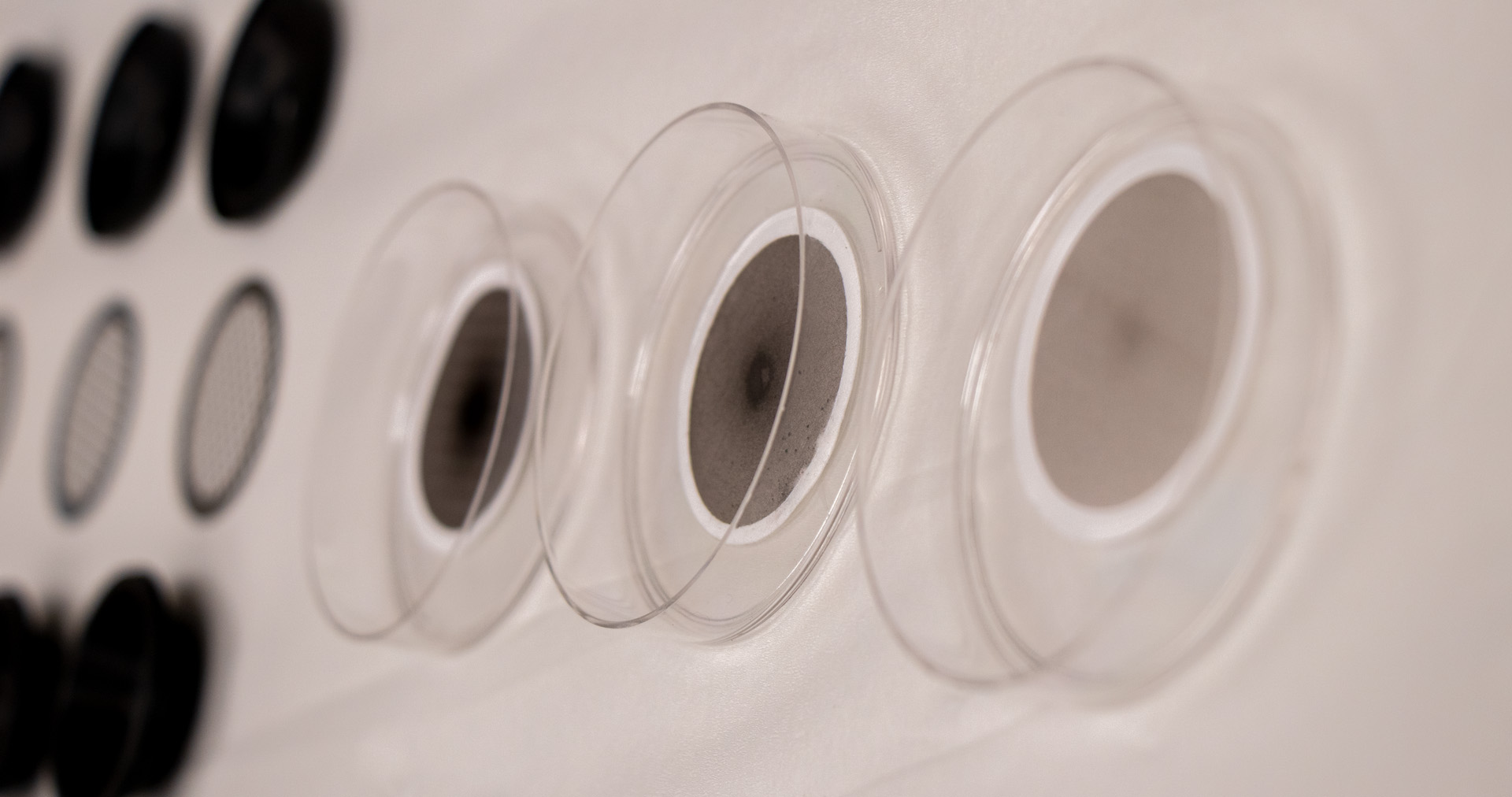

“It came about because during that research we identified many areas we didn’t understand. For example, we noted the inadequacy of currently approved monitoring technologies, such as being able to accurately monitor the effectiveness of controls and monitor exposure in real time.

“Another project under the program, which is being completed in conjunction with Nikky LaBranche, identified that it is very naïve to say ‘coal dust is coal dust’, because coal dust actually contains many, many chemicals. We are now asking questions about coal dust constituents and whether they potentially pose more of a threat than the carbon in coal dust.

“There is also a whole world of non-coal mining where, as an industry, we don’t have a very good feel for how particulate matter impacts the worker. Individual companies may have some idea, but because they are not organised like the coal sector with ACARP, and until very recently, there was no centralised collection of the data, we are concerned that the risk to health of particulates is not being effectively managed. Especially in a lot of metal mining companies where the metals themselves are active pollutants not just a passive dust.

“Of course, to interest companies we need to demonstrate why our research is necessary, and an enormous part of that is showing what is and isn’t known and what the issues are. To that end, over the next 6 month period we will be publishing as much as we can to get things in front of people.

“We are also proactively undertaking very important research, and Nikky in particular is trying to organise field work to quantify chemical compositions and size fraction analyses.”

Health and Safety challenges going forward

“The challenge industry faces at the moment is maintaining vigilance in an increasingly complex situation. At first glance a lot of things are improving, becoming safer, due to new technology like automation.

“But there is a need to recognise potential unintended consequences of some actions. If we are not thorough in our investigations and risk assessments we may gloss over issues. In addition there is a danger that automation could cause a loss of skill sets and practical knowledge. Controlling a haul truck from an air conditioned office in a remote location is very different to actually driving the vehicle.

“Yes automation can work very well, but if you only partly automate how do you manage automated alongside non-automated equipment? We have seen a number of accidents where automated vehicles have collided with non-automated vehicles.

“There is no doubt that health and safety in the industry has improved enormously over the last 20 years, but the challenge is to maintain that improvement.”