A new tool created by the Sustainable Minerals Institute’s (SMI) Centre for Mined Land Rehabilitation (CMLR) will enhance stakeholders’ understanding of how different mine site rehabilitation approaches can affect regional ecosystems.

Developed for use by the Office of the Queensland Mine Rehabilitation Commissioner, the tool uses a variety of data-informed environmental maps (i.e. data layers) to understand how two types of rehabilitation – rehabilitation to agriculture or restoration to native ecosystems –influence the surrounding ecosystems.

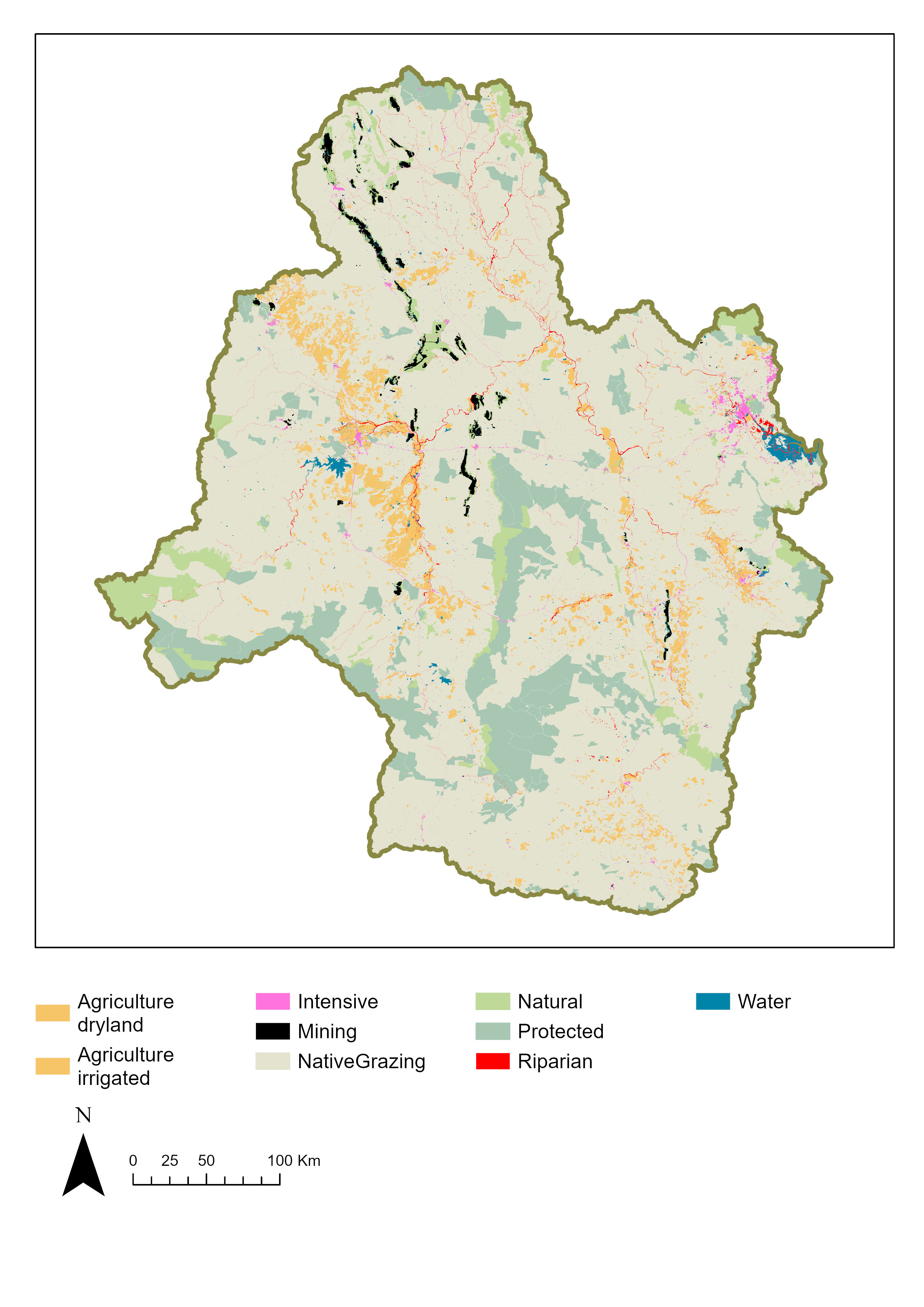

In a study accompanying its release, researchers apply the tool to mines in Queensland’s Fitzroy region, where more than 120,000 ha of land has been disturbed by mining.

Improving regional planning

CMLR Research Fellow Dr Lorna Hernandez-Santin said the tool allows for better informed, more cohesive, regional decision-making.

“There is increasing pressure on both government and the mining industry to improve biodiversity and ecosystems in mining impacted regions,” Dr Hernandez-Santin said.

“The tool we’ve developed can help achieve better biodiversity outcomes at a regional scale by providing the government with a data-based model of how the rehabilitation of individual mines could enhance connectivity of their landscapes.

“This is an important measure to counteract the impacts from fragmentation on ecosystems and individual species.

“The tool provides a three-level system – green, yellow, and red – to rate how connectivity could improve when choosing native restoration over agriculture rehabilitation.

“This allows the government to look at the value of these different rehabilitation forms at the local area of the mine, but also take a step back and look at the connectivity at a regional level.

More efficient industry decision-making

CMLR Centre Director Professor Peter Erskine said the tool can help companies make informed decisions about their rehabilitation.

“Intuitively, native restoration is the option which we found to be generally most beneficial. However, that was not the case for all areas,” Professor Erskine said.

“For some of the mines we looked at, particularly when situated with little remnant vegetation, it really didn’t make a large difference whether you use native restoration or just aim for agriculture level rehabilitation.

“That means that companies and government regulators can use this tool to collectively understand the cost-effectiveness and potential benefits from choosing different rehabilitation outcomes.”

The data behind the tool

“The connectivity model uses ‘circuit theory’ to indicate how animals move through the landscape based on which path has the least resistances, analogous to electric currents,” Dr Hernandaz-Santin said.

“The resistance in the connectivity model is derived from a species distribution model, which uses different data layers that were compiled from public and private databases, including elevation, climate data, species location data, vegetation cover data, and land use maps.

“It essentially shows you how likely you are to find an animal moving or a plant dispersing through an area based on the different variables in the layers.

“You can then apply the different environmental outcomes expected from mine site rehabilitation, each which has their own effect on the variables, to see how they may affect connectivity.

“In this case, the tool is based on a combination of fauna and flora, which provides a good biodiversity snapshot, but you could also use this approach to focus on specific species.”