War on mine waste

As I stepped out of the fancy hair salon recently, I felt sick. Not because I had spent a little too much money on something I could have gone to the high street for, but because of the amount of foil that had been used to colour my locks.

I asked the colour technician ‘how much foil do you use per week, or order in a month?’ I didn’t get a clear answer but on doing some quick research I discovered that the Australian hair industry sends over 1000 tons of foil waste to landfill annually with only 1% of salons recycling. The ABC’s war on waste highlighted this with Gerrard McClafferty’s personal campaign to collect and recycle these in Western Australia.

However, what had yet to be highlighted is the waste footprint leftover from producing the foil in the first place. Red muds are the most common waste associated with the production of aluminium and it’s de-risking through transformation has been the focus of research for Professor Longbin Huang and his team for many years.

As I sat in the salon chair waiting for the foils to be taken out, I contacted Professor Huang to ask just how much red mud might be produced as a result of the hair industry’s foil consumption. He calculated that for every 1 ton of Al foils, we need to mine at least 4-5 tons of bauxite ores which can leave behind about 2-3 tons of alkaline and saline red mud. What does that equate to? Think an orca or a Ford F-250. While this isn’t perhaps the biggest mine-waste related footprint, it was certainly enough to make me feel uncomfortable because as a consumer, and working in this particular field, I hadn’t really thought it through until this experience.

While there are opportunities for metal recovery from red muds, for example scandium, gallium and germanium (the latter two of which have been in the news a great deal over these past few weeks), PhD student Long Ma presented another potential management option – growing wheat on red mud.

While I am not sure what the appetite will be in the years to come for ‘red bread’ or even ‘red beer’ it certainly highlighted that this type of thinking and testing is what is needed to find different strategies to win our ‘war on mine waste’, a narrative that needs to grow as the country once again engages in the war on waste campaign and one I presented on at last year’s Geohug: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lgy5SN6tVHc

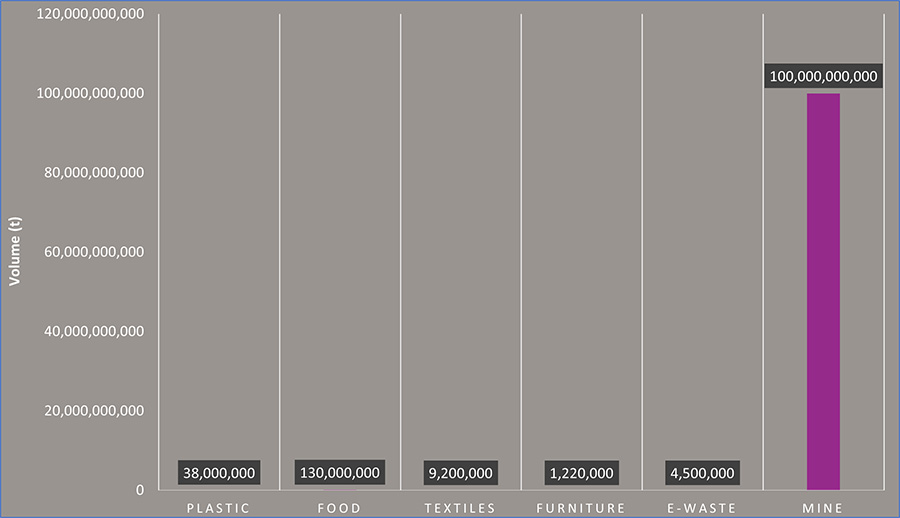

A back of the envelope combined with quick research confirms that the waste footprint of mining industries are in greater magnitudes than that for other industries (e.g., plastics, food, textiles, furniture, e-waste).

Yet, as consumers we are less likely to ask the question when buying products – what happens to the mine waste associated with making this? Inspiring and empowering consumers to make decisions based on this may be transformational when it comes to mine waste management and may even drive more secondary prospectivity programs globally.

I thoroughly encourage everyone working in the mining sector or mine waste directly to use the #waronminewaste to raise awareness and enable our society to have a better perspective of our true-waste footprint, not just those we encounter as end-users.