Lead will lead us to find critical minerals

We all have expectations and prophecy about how things will go, but we can't always predict challenges. Sometimes, they come up because of decisions we made that have little or no interaction with what is waiting for us.

Being a good field researcher is about more than just studying and reading. I believe it is important to interact with the people and the area where you're going to explore. This philosophy was a key part of my first fieldwork in Australia which took place in July 2024. Additionally, adopting a ‘take-5 approach’ is crucial whereby the sampling site is assessed for risks (and in Northeast Queensland this can also include checking for exotic wildlife!). After which, the hunt for interesting samples begins.

In Northeast Queensland, there are many abandoned mine sites that could be valuable resources in the future in terms of critical mineral endowment. People in this region, historically, were reliant upon this mining sector with many locals having family members who own or worked in the mines. Over the course of this week-long trip, our aim was to sample several smaller mine workings around the Baal Gammon and Jumna mine sites (Figure 1) with a primary focus on determining indium, tin and copper content in waste rock materials

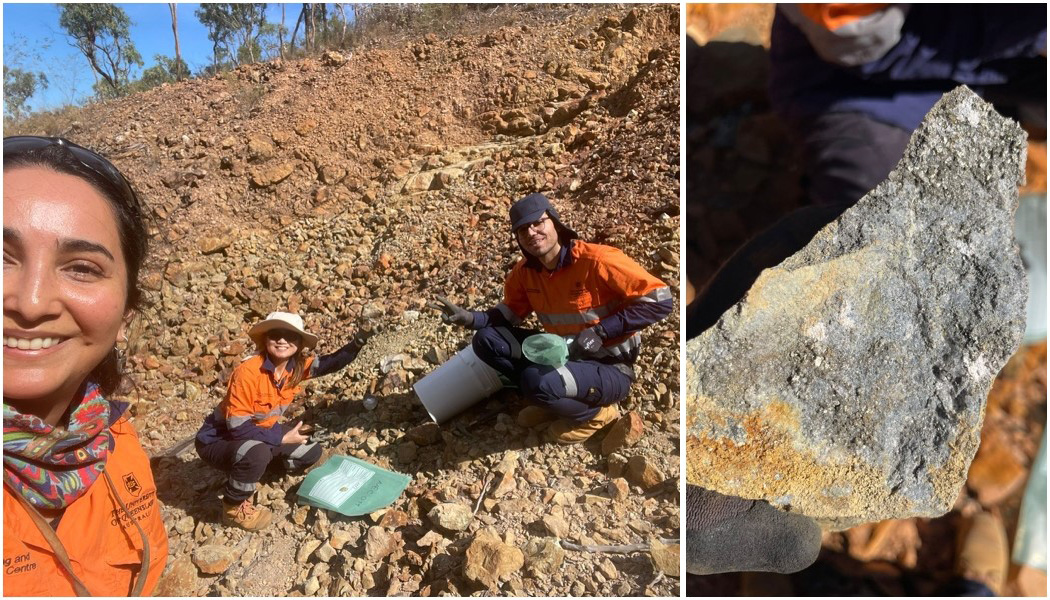

Our journey began with meeting Senior Project Officer Mitchell Thompson (Senior Project Officer, Department of Resources), whose expertise in visiting mine sites in this area was critical to the success of this campaign. Under his guidance, we had the opportunity to visit several abandoned, and not widely known, mine waste sites. Our first target site was Montalbion (Figure 2) followed by Victoria (Figure 3), hidden in the middle of bushland. The drive to this site gave Lexi K’ng (Principal Research Technician, Sustainable Minerals Institute) a chance to put into practice the skills learnt on the 4WD course she took last year. As we explored waste rock piles at both sites, we found potentially valuable minerals such as galena, chalcopyrite and pyrite which are sources of base, critical and precious metals (i.e. Pb, Bi, Ag, In and Cu) and so were sampled.

Prior to this fieldtrip, research undertaken by Olivia Mejías (PhD candidate, Sustainable Minerals Institute) had identified biogenic indium-rich samples at the Baal Gammon mine site, located in this region. Motivated by her findings, we accompanied colleagues from the Australian Institute for Bioengineering and Nanotechnology (AIBN) at The University of Queensland (UQ) led by Dr Paul Evans (ARC Future Fellow, UQ School of Chemistry and Molecular Biosciences) to collect more of these samples for more biological studies (Figure 4). The assistance of the Baal Gammon remediation team was critical to ensure the safe collection of these samples (Figure 5). We also explored the Confederation site with the help of Site Operator Brad Ward. Along with Mitch, we located an abandoned area containing a lot of valuable waste rock (in terms of secondary prospectivity targets) which were representatively sampled.

On the last day of our fieldwork, while it was cloudy, we were lucky it did not rain until we finished our sampling. We explored abandoned sites around Herberton, with numerous underground mine sites encountered. While we identified several potential sampling sites, the abundance of secondary prospectivity target samples was far fewer than the sites sampled earlier in the trip. Despite this, several samples (massive sulphides and quartz veins) were collected for this study.

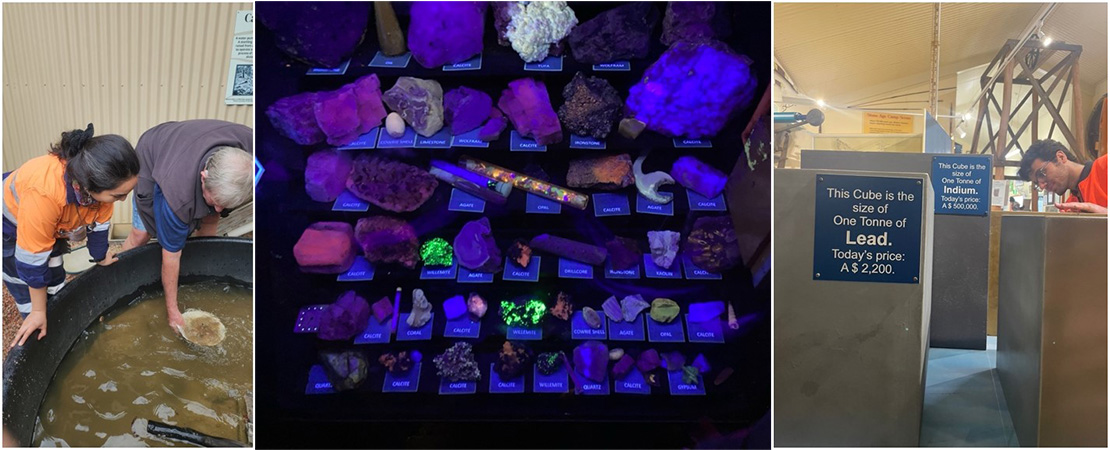

At the end of the campaign, we were encouraged by Mitch to visit some historical mining works and infrastructure near Irvinebank town. It was fascinating to see that most of the mine sites in this region were discovered over 100 years ago and had a rich history. Motivated by this experience, our last stop was at the Herberton Museum (Figure 6), run by very friendly and knowledgeable volunteers. Our tour guide at this museum, Graham, generously shared his knowledge, giving us insights into mining and mineral processing methods used in Australia, and more specifically this region, since late 1800s (Figure 7). It was such an invaluable experience providing us with context for our secondary prospectivity research, I encourage everyone to pay a visit at least once in your lifetime!

In summary, my first field research trip was truly memorable. During the trip, I sampled interesting waste rock collected from abandoned mine sites and we even collected some native plants for a sister-project. I also had the opportunity to meet fascinating people during this journey, several of which were experts in remediation and the history of Northeast Queensland. I feel lucky to be exploring the potential of mine waste with the MIWATCH team and motivated to develop pathways to extract metals from these wastes in our UQ labs. I wish to also acknowledge the assistance provided by Kobie Johnson (Project Officer) from the Abandoned Mines Lands Program for his expert assistance with the identification of potential sample locations, logistics for organising access needed to complete this fieldwork.